If you’re familiar at all with our approach to supporting infant movement development, you’re likely aware that a main focus of our work is teaching infant touch and handling skills to parents and other caregivers. (If you’re not familiar, read more about our Preparing for Caring project.)

We’d like to share a bit of context and history about our handling suggestions. Where did they come from? The short answer is that we didn’t make them up! There’s history behind them, though we do like to think we’ve honed, curated and elaborated upon them over the years.

The longer story is that we learned and practiced touch and handling skills in our training as Infant Developmental Movement Educators (IDMEs) through the School for Body-Mind Centering®.

The IDME training program, which teaches observation and facilitation skills in working with babies, was developed in the early 2000s by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, with support from Sandra Jamrog and Lenore Grubinger, who together drew on wide and deep experience supporting infant movement development, birth, and lactation.

In addition, Bonnie earlier had trained and worked as a pediatric occupational therapist. She spent time studying with Berta and Karel Bobath, known for their rehabilitative approach to working with people (adults and babies) with neurological challenges, including cerebral palsy and stroke. Long after she left institutional medical settings, Bonnie continued to work with babies with special needs as well as “typically developing” babies.

It’s a commonly held principle that understanding typical development is key in assessing and supporting delayed or atypical development. The influence and feedback loops can go both directions. While the IDME program focuses on training people to work with babies in the typical range, it’s been informed and enriched by Bonnie’s education and experience with babies with different abilities.

Here are two examples from clinical settings where touch and handling techniques developed for vulnerable babies can be applied to all babies.

A familiar example might be kangaroo care, which encourages skin-to-skin contact after birth and in the early weeks. It was first recognized (or re-discovered) as an effective way to support prematurely born and otherwise vulnerable infants in the 1970s in Colombia. Kangaroo care made a clear and measurable difference in struggling babies’ ability to survive and thrive. From there, it has become widely popularized as a best practice in support of bonding and co-regulation for all newborns and their caregivers.

Another example is side-lying for young babies, which is a common practice in NICU-like settings . We also recommend side-lying for young babies, even though it is not yet well-known outside of NICU settings. Since this has proven to be a helpful option for vulnerable babies, why not make it available as a resource for all babies, even if the difference it makes might not be as stark?

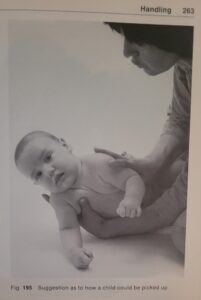

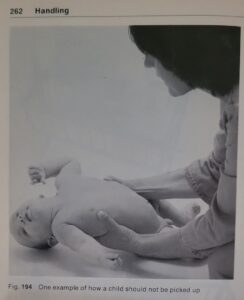

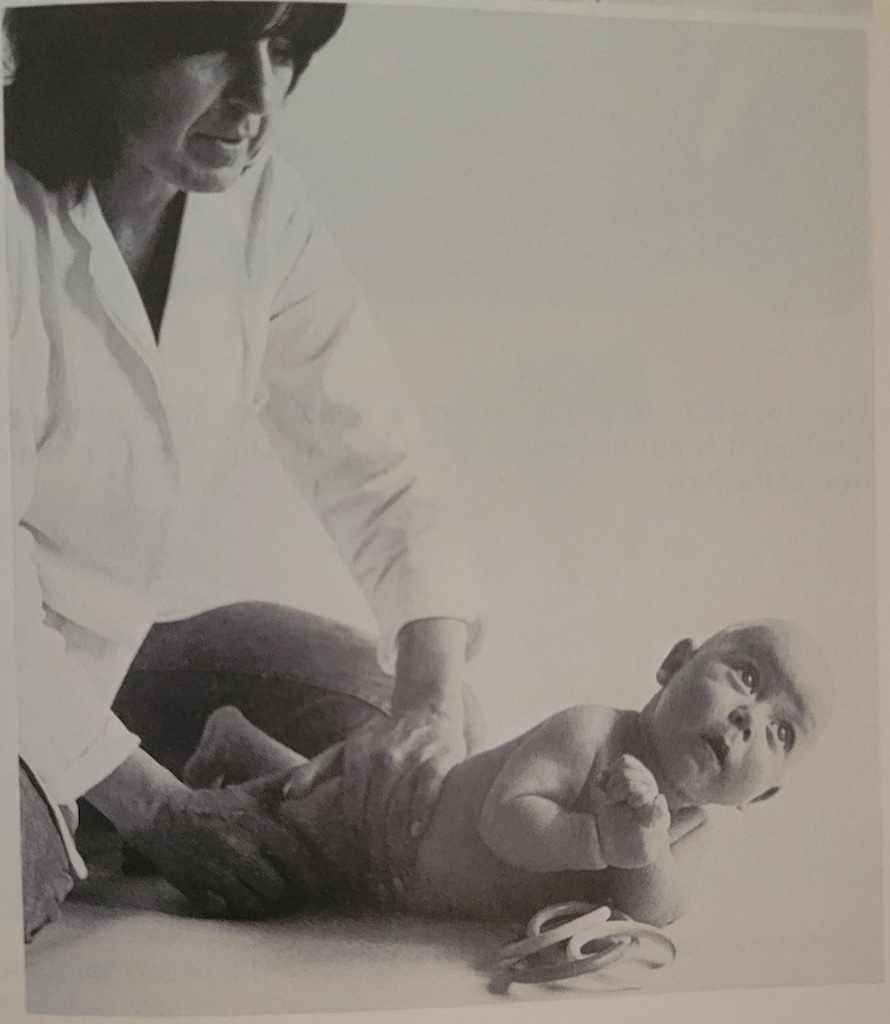

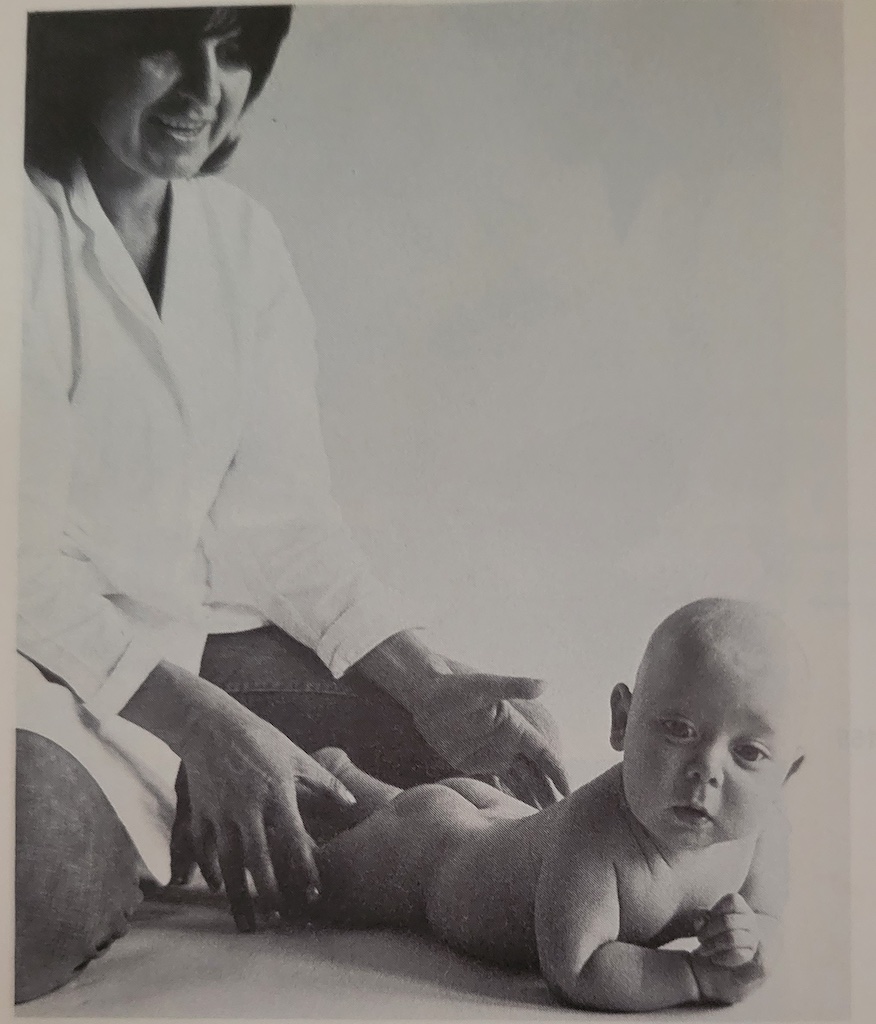

Other handling skills we teach echo others’ early work with children with developmental challenges. Below are a few images from a medical textbook we have titled Normal Infant Development and Borderline Deviations. It was originally published by Thieme in 1979 in German, translated to English (in its 4th edition) in 1992, and is no longer in print. The book was written by Inge Flehmig, M.D., a German pediatrician who also happened to train in the Bobath method. Her book, aimed at pediatricians and other child development professionals, details normal infant development and offers a guide to early signs of atypical development.

The final chapter is called Handling, with tips that doctors can show to parents. (We’re thrilled that a textbook on infant development actually has a chapter on handling!) Here are the opening sentences of the chapter:

Before being able to walk about freely, all children are intensively subjected to the mother’s handling. In children that display deviations in their motor development, that handling can have considerable influence on the child’s further development.

Acknowledging its dated language and assumptions, it would take only minimal reframing to succinctly articulate why we teach handling skills:

Before being able to walk about freely, all children are intensively subjected to their caregivers’ handling. Handling can have considerable influence on the child’s further development.

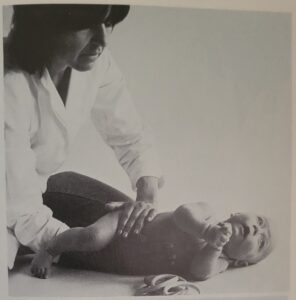

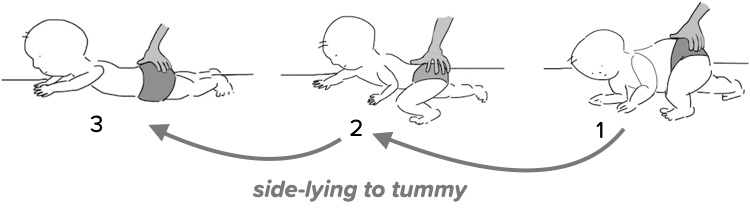

The photos below are from the book, and show suggestions for 1. picking up a baby through side, and 2. what to avoid in picking them up. They match our recommendations, as shown in illustrations from our Preparing for Caring handout.

As we continue to learn more about the history of this field through research and connecting with other professionals, we’re delighted to keep finding places where we overlap with other practices. We feel grateful and privileged to be part of a (not necessarily linear) lineage of infant care-giving and developmental wisdom.

We welcome your comments and questions.

* * *

Hi, Wonderful job, such a guidance is truly needed! I saw few very old videos on YouTube also showing how to handle babies (I think American), and in my opinion video or real life photo is the best way to present it – although the drawings are pretty, I don’t think that a parent who has no physio knowledgeable will get the point of where and how to support from such a simplified drawing